The Arrangement of the Psalms in Book 1

[This article is best viewed on a desktop computer]

A casual reading through the Book of Psalms might give one the impression that there is very little organization to the overall arrangement and ordering of each individual psalm in relation to the entire collection. The psalmist moves from lament to praise, from coronation psalms to confessions, from liturgical hymns to cursing enemies without any warning. Attempts to read straight through the Psalms can be met with frustration due to the apparent random nature of its organization and structure.

However, a careful analysis reveals a multi-layered, subtle, and profoundly meaningful structure and arrangement of the entire book. This arrangement is apparent in all five Books of Psalms, but it is particularly striking in Book I, Psalms 1-41. Keys to understanding the arrangement of the psalms are the awareness of chiasms, the linking together of psalms with common themes, words, and thought development, and the use of symbolic numbers.

Chiasm

One of the features of Hebrew poetry is the chiasm. A chiasm can occur in a single verse (Psalm 2:10)

Therefore, you kings, be wise; A (kings) B (be wise)

be warned, you rulers of the earth B1 (be warned) A1 (rulers of the earth)

Connecting the lines between each corresponding thought creates an x-shaped pattern called a chiasm or chiasmus. It resembles the Greek letter chi. In this case, it is called a four-point chiasm.

Chiasms can also form the structure of an entire psalm. For example, Psalm 2 contains four stanzas of three verses each with the following themes:

A Actions on earth: The kings of the earth speak/warn God (vss. 1-3)

B Actions in heaven: God speaks (vss. 4-6)

B1 Actions in heaven: The Anointed One (Son of God) speaks (vss. 7-9)

A1 Actions on earth: Kings be warned (vss. 10-12)

In this case, the structure is considered a two-point chiasm, and the force is to draw attention to the central verses of the psalm, in this case, the installation of God’s Anointed as King on Zion (vss. 6,7).

Chiasms can be spotted by observing two aspects of the psalm. First, look to see if there are common words and ideas that frame the psalm. Begin looking at the first and last verses of the psalm. Second, look to the center of the psalm is determine if the key thought may be found there. A good example of this structure is found in Psalm 8 (NIV, 1984):

A (frame) 1 O LORD, our Lord,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!

B (heavens) You have set your glory above the heavens.

2 From the lips of children and infants you have ordained praise

because of your enemies, to silence the foe and the avenger.

3 When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars, which you have set in place,

C (mankind) 4 what is man that you are mindful of him,

the son of man that you care for him?

5 You made him a little lower than the heavenly beings

and crowned him with glory and honor.

B1 (earth) 6 You made him ruler over the works of your hands;

you put everything under his feet:

7 all flocks and herds,

and the beasts of the field,

8 the birds of the air,

and the fish of the sea,

all that swim the paths of the seas.

A1 (frame) 9 O LORD, our Lord,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!

The psalm is framed by the glory of Yahweh [A and A1], (“O LORD, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth!), and the glory of man [C] (crowned with glory and honor) is placed in the center (vss. 4-5), between heaven [B] and earth [B1]. Thus, the chiastic structure reinforces the central message of the psalm, namely, that mankind, while small in comparison to the vast glory of God in the cosmos, has been granted authority to rule over earth as God’s co-regent.

This chiastic construction is not used in every psalm by any means, but it is common enough to be notable. It is different from the typical linear development of western thought, and it forces the reader to examine the psalm forwards and backwards, rather than just jump to the end for the conclusion.

Common Themes, Words, and Thought Development

A second clue in discovering the organizational thought behind the ordering of the psalms is to look for common themes, words, and development of thought. For example, the temple is referenced in some way in every psalm from 24-29, and psalm 30 is designated as a psalm for the dedication of the temple, suggesting a topical grouping. Psalms 20 and 21 are both royal psalms – the first a congregational prayer for victory for the king, the second, a response to the congregation by the king. These are just a few examples of the identifiable connections between one psalm and another.

The Symbolic Meaning of Numbers

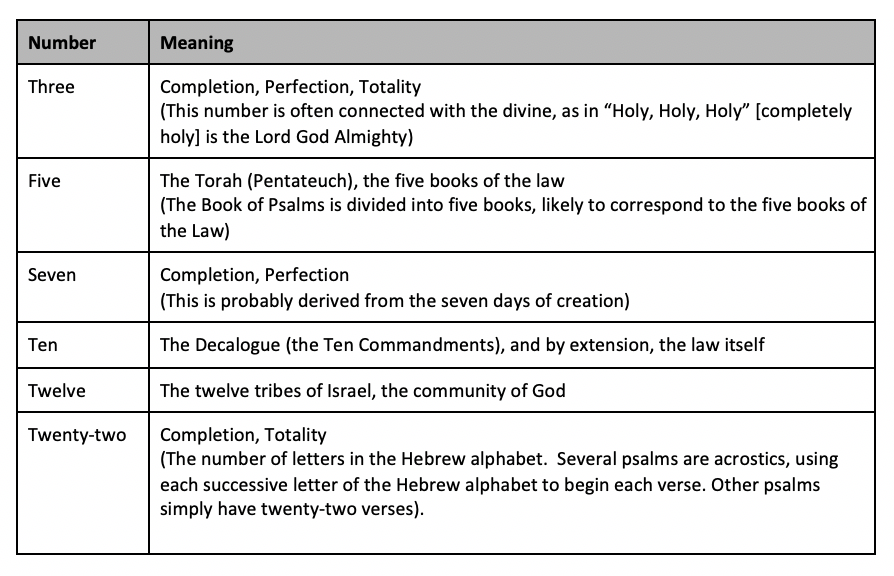

A final clue to the arrangement of the psalms has to do with the use of symbolic numbers. It has been well-noted that certain numbers often have symbolic significance in the Bible. While it is not true in every case, the following symbolic meanings are generally agreed to be connected to these numbers:

One must be careful not to read too much into these numbers, as some have done, purporting to discover some kind a secret Bible code. This is not what we are looking for when we study the Psalms, so one must use caution in placing too much meaning on the poetic use of numbers. It is possible to find patterns that may be merely coincidental. However, I believe there are enough patterns in the numeric arrangement of the psalms to make the case that the symbolic meaning of numbers played some role in the final shaping of the Psalter.

The Chiastic Arrangement of Psalms 1-14

The first fourteen psalms display strong evidence of a chiastic arrangement as shown below:

1-2 Wisdom and Folly (Individual and National)

3-7 Five Laments

8 Hymn of praise

9-13 Five Laments

14 Wisdom and Folly

If one reads the first two psalms together, it’s obvious that they relate to one another. The first psalm presents a contrast between the wise and the foolish person in its appeal to choose the way of the righteous. The wise person avoids the counsel of the wicked and seeks the wisdom of God in the Torah, whereas the foolish person takes no care and quickly perishes because of it. The second psalm offers the same contrast between the wise and foolish, although here it begins with the actions of a foolish nation and ends with the actions of a wise nation. The foolish people rage against Yahweh and his Anointed King, while the wise society shows appropriate respect to God and his king.

A The Wise Man (1:1-3)

B The Foolish Man (1:4-6)

B1 The Foolish Nation (2:1-3)

A1 The Wise Nation (2:10-12)

One can see from this analysis that the first two psalms taken together are framed by wisdom. In addition, the center of the first psalm is the Torah [vss 2-3] which is the wisdom and revelation of God, while the center of the second psalm is the reign of God through his Son [vss 6,7], “I have installed my king on Zion”. These two themes, the wisdom of God and the reign of God, are woven throughout the entire book of Psalms, and whoever shaped the final arrangement of the Psalter meant to communicate these two themes from its very beginning.

As an additional note, we observe that the second psalm has twice as many verses (12) as the first (6). This doubling of the number of verses reminds the reader that what is true of the individual (Psalm 1, singular) is true of the nation (Psalm 2, plural).

The next psalm that contrasts the wise and foolish is Psalm 14. It begins with the declaration: “The fool says in his heart ‘There is no God’”. It’s not that the fool is an atheist, as it is unlikely there were any true philosophical atheists during the days of the psalmist. Rather it is that he is a practical atheist, living as if there were no God. The fact that this psalm is repeated again with just a few alterations as Psalm 53 suggests that it is serving a particular a purpose in the overall arrangement of the Book of Psalms. A logical conclusion is that it serves as a frame to the first fourteen psalms.

Thus, if the first fourteen psalms are a chiasm framed by Psalms 1,2 and 14, then the psalm that is central to the first fourteen psalms is Psalm 8. Psalm 8 also happens to be the first hymn of the Psalter. It is a communal song of joyful praise abruptly breaking the pattern of lament set in Psalms 3-7. There are five psalms of lament that precede Psalm 8, and five that follow. It is significant to note that Psalm 9 and 10 are actually one psalm that has been divided in the final editing of the Psalms. Not only do these two psalms share a common theme (justice), but they are both acrostics (structured on the successive letters of the Hebrew alphabet) with Psalm 10 continuing where Psalm 9 leaves off alphabetically. The mystery of why the psalm was divided into two separate psalms is solved when one realizes that this functions to create the numerical balance of the chiasm of Psalms 1-14 with five psalms on either side of Psalm 8.

Thus, with Psalm 8 as the central psalm of the first chiasm in Book 1, the focus is drawn to its central theme, namely, the glory of God and the dignity of humanity ordered under Yahweh’s reign. The psalm declares that mankind, while small in comparison to the cosmos, is exalted as a co-ruler with God, crowned with glory and honor, ruling over the works of God’s hands. This theme is simply another statement of the truths expressed in the psalms that form the frame of the chiasm: Psalm 1: Blessed is the one who lives according to God’s rule; Psalm 2: Blessed is the nation who submits to God’s rule; and Psalm 14: God is a refuge for his covenant people when fools seem to rule the world.

The Chiastic Arrangement of Psalms 15-24

The next ten psalms also demonstrate evidence of a chiastic structure in their arrangement. Based on the genre of each psalm, a chiastic structure emerges which places Psalm 19, the second hymn of the Psalter, at the center.

15 Entrance

16 Trust

17 Lament

18 Royal

19 Torah Hymn

20-21 Royal

22 Lament

23 Trust

24 Entrance

In this case, the chiasm is framed by the entrance psalms 15 and 24. An entrance psalm is a liturgy for approaching God in corporate worship that typically involves a call and response (a question from the leader and an answer from the congregation). For example,

Psalm 15:1 asks:

“Who may dwell in your sanctuary? Who may live on your holy hill?”

Psalm 24:3 asks again:

“Who may ascend the hill of the YHWH? Who may stand in his holy place?

Psalm 24:9 provides the ultimate answer:

“Lift up your heads, O you gates;

lift them up you ancient doors,

that the King of glory may come in.”

From the entrance psalms, the chiasm moves inward to the trust psalms 16 & 23 which also have much in common with each other including the themes of refuge, cup, and presence.

Keep me safe, O God

for in you I take refuge (16:1)

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil, for you are with me (23:4)

You have assigned me my portion and my cup…

The boundary lines have fallen for me in pleasant places (16:5,6)

You anoint my head with oil; my cup overflows (23:5)

You will fill me with joy in your presence,

with eternal pleasures at your right hand. (16:11)

I will dwell in the house of the LORD forever (23:6)

These two trust psalms frame the laments of 17 and 22 in which the psalmist cries to God for rescue from his enemies.

They are like a lion hungry for prey, like a great lion crouching for cover…

Rescue me from the wicked by your sword (17:12,13)

Roaring lions tearing their prey open their mouths wide against me…

Rescue me from the mouths of the lions (22:13,21)

The lengthy psalm 18 is generally classified by genre as a song of thanksgiving. It is David’s testimony of God’s deliverance of him in battle and his favor on him as king. For this reason, it may also be considered a royal psalm with a focus on YHWH securing the kingdom for David and his descendants forever. The final verse sums it up:

He gives his king great victories;

he shows unfailing kindness to his anointed

to David and his descendants forever. (18:50)

Together with Psalms 20 (a prayer for the king to be victorious) and 21 (a response from the king praising God for victories granted), these three royal psalms frame Psalm 19, the central psalm of the second chiasm. Like the first hymn of the Psalter (Psalm 8), this second hymn (Psalm 19) speaks of YHWH’s glory in creation and man’s responsibility to live in a covenant relationship with him. The psalm expands on the meditation of the Torah first introduced in Psalm 1:2-3, and it provides a glimpse of what is to come in the magnificent Torah psalm, Psalm 119.

The Chiastic Arrangement of Psalms 25-34

Like the second chiasm, the third chiasm of Book 1 also contains ten psalms. Here the order is not quite as obvious, but it is still clearly discernible. In this case the chiasm is based on both the poetic structure (it is framed by two acrostic psalms) and on the content (corresponding themes) of each psalm.

25 Acrostic

26 Innocence (“I wash my hands in innocence”)

27 Trust (“I am confident of this”)

28 “Hear my cry!”

29 Hymn (YHWH reigns over the storm and flood)

30 “Thanks for answering!”

31 Trust (“Into your hands I commit my spirit”)

32 Guilt (“you forgave the guilt of my sin”)

33 Song of praise (22 verses)

34 Acrostic

The acrostic structure in Hebrew poetry incorporates each letter of the Hebrew alphabet in succession as the starting letter of each verse. The Hebrew alphabet thus provides a predictable framework for the entire psalm. However, it also constrains the poet in such a way that it can be difficult to maintain thematic unity. As acrostics, Psalms 25 and 34 share elements of lament, trust, praise, and wisdom, but do not have a dominant theme. The use of the acrostic structure, because it includes every letter of the alphabet, has the subtle force of communicating completeness and totality. While Psalm 33 is not an acrostic, it does consist of 22 verses, giving it the same length as an acrostic and the same force of completeness. The psalm is a call to worship YHWH as God of creation and God of covenant within the balanced poetic framework of a call to worship and a vow of trust framing the two central stanzas. It has the force of an acrostic without the limitations that the acrostic structure imposes.

Moving to the next two psalms within the acrostic frame, Psalms 26 and 32 also demonstrate correspondence to one another. The first is a declaration of innocence:

I wash my hands in innocence, and go about your altar, O YHWH (26:6)

While Psalm 32 (a penitential psalm) is a declaration of guilt:

Then I acknowledged my sin to you and did not cover up my iniquity.

I said, “I will confess my transgressions to YHWH”

-- and you forgave the guilt of my sin. (32:5)

While antithetic to one another, these two psalms clearly complement one another and are an example of antithetic parallelism within the ordering of the psalms themselves within a chiastic framework.

The next frame consists of two psalms with corresponding themes of trust. Psalm 27 declaring:

YHWH is my light and my salvation -- whom shall I fear?

YHWH is the stronghold of my life -- of whom shall I be afraid? (27:1)

I am confident of this:

I will see the goodness of YHWH in the land of the living. (27:13)

This corresponds with the frequent declarations of trust found in Psalm 31:

In you, O YHWH, I have taken refuge (31:1)

Into your hands I commit my spirit (31:5a)

But I trust in you, O YHWH; I say, “You are my God”

My times are in your hands (31:14,15a)

These two psalms of trust then form the frame for two corresponding psalms of lament and thanksgiving. In the Psalm 28, the psalmist begins his lament with this prayer:

To you I call, O YHWH my Rock;

do not turn a deaf ear to me.

For if you remain silent, I will be like those who have gone down to the pit.

Hear my cry for mercy as I call to you for help,

as I lift up my hands toward your Most Holy Place (28:1,2)

Psalm 30 is the psalmist’s joyful expression of thanksgiving to God for hearing and answering his prayer:

I will exalt you, O YHWH, for you lifted me out of the depths…

O YHWH my God, I called to you for help and you healed me.

O YHWH, you brought me up from Sheol;

you spared me from going down into the pit. (30:1,2)

Once again these two psalms are not synonymous in theme but there is clearly a correspondence of prayer and then thanksgiving for answered prayer. Thus, in this ten psalm chiasm the arranger of the psalms moves from acrostic parallelism (Psalms 25 and 34) to antithetic parallelism (Psalms 26 and 32), to synonymous parallelism (Psalms 27 and 31), to synthetic parallelism (Psalms 28 and 30).

The force of this chiastic structure is to draw the focus on the central psalm of the chiasm, Psalm 29, notably the third hymn of the Psalter. Like the two previous hymns that served as the central point of their chiasms (Psalms 8 and 19), Psalm 29 declares God’s sovereignty and glory over creation and calls all to live within the framework of his reign:

The voice of YHWH is over the waters;

the God of glory thunders, YHWH thunders over the mighty waters. (29:3)

And in his temple all cry, “Glory!”

YHWH sits enthroned over the flood;

YHWH is enthroned as king forever.

YHWH gives strength to his people;

YHWH blesses his people with peace. (29:9b-11)

The three creation hymns (8,19,29) serve as foundational statements of the reign of YHWH and the importance of the ordering of all human life under his authority and in covenant relationship with him. They also happen to be positioned as the central psalms in the first three chiasms of Book 1.

The Chiastic Arrangement of Psalms 35-41

The final chiasm in Book 1 takes a quite different turn from the first three. The structure is not quite as clear as the previous chiasms, but it is evident from corresponding thematic elements that these seven psalms are connected by the common thread of lament due to betrayal and corresponding vows of trust.

35 Betrayal

36 Praise and Trust

37 Wisdom and Trust (a double acrostic)

38 Pain (22 verses, but not an acrostic)

39 Lament and Trust

40 Thanksgiving and Trust

41 Betrayal

The seven-psalm chiasm is framed by Psalms 35 and 41, prayers for vindication in the face of betrayal by false friends:

Contend, O YHWH, with those who contend with me (35:1a)

Since they hid their net for me without cause

and without cause dug a pit for me (35:7)

let not those who hate me without reason maliciously wink the eye (35:19b)

Vindicate me in your righteousness, O YHWH, my God (35:24a)

In Psalm 41 the psalmist describes the most painful betrayal of all,

Even my close friend, whom I trusted,

he who shared my bread,

has lifted up his heel against me. (41:9)

It is significant to note that both Psalms 35 and 41 are referenced in the New Testament in connection with the enemies of Jesus (35:19 / John 15:25) and the betrayer Judas (41:9 / John 13:18).

In the context of betrayal by false friends, the psalmist offers laments that are filled with moments of praise, wisdom, thanksgiving and ultimately trust. There is a common thread of trust in the midst of the pain that weaves its way through all seven of these psalms.

The central psalm of the chiasm is Psalm 38, one of the seven penitential psalms (6, 32, 38, 51,102, 130, and 143). It consists of twenty-two verses, and although it is not an acrostic, the use of twenty-two verses has the force of communicating completeness. The psalm is almost entirely a complaint framed by requests for help with a solitary note of trust in verse 15, “I wait for you, O YHWH; you will answer, O Lord my God.”

This central psalm stands in stark contrast to the great creation hymns that serve as the center of the first three chiasms in Book 1. From the perspective of the psalmist, it seems as if the world ordered within the glory and sovereignty of God (Psalms 8, 19, and 29) is undone by the evil that resides in the heart of men (Psalm 38). That Jesus identifies himself with Psalm 38 by referencing it in relation to his own enemies (38:19 / John 15:25) is a powerful reminder that the God of glory and creation is in Jesus, “despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows, and familiar with suffering” (Isaiah 53:3). This gives great comfort to those who have put their hope in him (Psalm 39:7), and it is the ultimate answer to the psalmist’s cries for help in these seven psalms.

Conclusion

It is clear that the arrangement of the psalms in the order that we find them was no accident. The final compiler of the Book of Psalms used features of Hebrew poetry (chiasm, common themes, genre, and symbolic numbers) to communicate central truths about the nature of God and his relationship with humanity. The four chiasms of Book 1 are also easily remembered because of the symbolic numbers associated with them.

Chiasm 1 - 14 psalms (a multiple of 7)

Chiasm 2 - 10 psalms

Chiasm 3 - 10 psalms

Chiasm 4 - 7 psalms

Perhaps by employing the symbolic numbers 10 (law) and 7 (completeness) the compiler is communicating the central Hebrew worldview that YHWH is complete and perfect and has ordered creation in such a way that life might flourish according to his divine laws. When that order is broken by the rebellion and betrayal of man, he himself came in Jesus Christ to redeem and restore creation to wholeness and order.